|

Many public art projects are slated for this month’s 50thanniversary of the Cuyahoga River fire and the clean-water movement it spawned. But only one connects that 1969 environmental catastrophe and the current day one caused by our jeans and the dye that makes them blue.

“Indigo is the color that we know because of our denim,” says Jessica Pinsky.

She is the founder and director of Praxis Fiber Workshop, in Cleveland’s Waterloo Arts District on the East Side.

“And most of that denim is being dyed with the synthetic version of indigo which uses lye as its activating ingredient. It’s incredibly toxic,” she says. “So we’re trying to make a movement towards using the natural version, which is much safer and healthier for environment.”

According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, textile mills generate one-fifth of the world’s industrial water pollution. In places like China, India and Southeast Asia, where regulations are few or rarely enforced, clothing manufacturers treat rivers like a waste pipe, like we once treated the Cuyahoga. Google “textile industry pollution,” and you’ll see disturbing photos of multi-colored rivers that environmental watchdogs say also flow with long-lasting and toxic chemicals. Recent documentaries like “River Blue” have raised the alarm:

RiverBlue – Official Trailer from RiverBlue on Vimeo. “We are committing hydrocide. We’re deliberating murdering our rivers.” “Our rivers across the world are being deeply impacted by the dumping of poisonous toxic material.” “Every single clothing you buy comes at a cost.” Whoooommmm, hums the soundtrack, ending with an ominous tone.

Now, no one would confuse the little arts non-profit Praxis Fiber Workshop, with its 17 human-powered floor looms, of being a textile factory. But Pinsky says Praxis cannot ignore what’s going on.

Kamora Davis, 12, holds up her bound bundle of cloth that she has pulled from the natural indigo dye vat at Praxis Fiber Workshop during a workshop on May 3, 2019. [Amy Eddings / ideastream]

“As a textile organization we feel like we have a debt to the rest to the greater textile industry and we feel like the education has to be about the full picture, and fashion and clothing is a part of that,” Pinsky says.

Last year, in a nearby vacant lot, she started a garden to grow plants for natural dyes with marigolds for yellow dye, amaranth for red and lots and lots of indigo, the oldest known natural dye. This year’s garden will hold even more. Kimmie Lessman, with the Cleveland Seed Bank, helped Praxis by getting indigo seedlings started at a hoop house on the West Side, watering them every day.

Cleveland Seed Bank’s Kimmie Lessman waters trays of indigo seedlings at a hoop house in Cleveland’s Stockyards neighborhood. They were transplanted a month later in May into Praxis Fiber Workshop’s natural dye garden [Amy Eddings / ideastream]

“So we’re looking at 85 trays of indigo,” she said, filling up a watering can from a rain barrel in the hoop house.

I asked her how many individual plants the trays held.

“We’re hoping that it translates into 8,000 to 9,000 seedlings. Yeah, we’ve completely doubled what we did last year, and then some,” she said.

The leaves from last year’s crop have been dried, soaked and allowed to ferment. The dye is being used in the art piece that Praxis is creating for the Cuyahoga50 celebration.

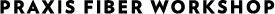

A rendering of what the Praxis indigo banners will look like when suspended from the Detroit Suprior Bridge. [Courtesy of Jessica Pinsky]

It’s hundreds of squares of cotton, dyed in indigo and stitched into three, 60-foot banners that will hang from the lower deck of the Detroit Superior Bridge, which spans the Cuyahoga near its mouth at Lake Erie. Pinsky asked four artists to design the banners and she’s hosted nine workshops around the city, asking the public for help dyeing the squares.

At a Praxis workshop, Theresa Yondo lowered her cloth into the warm, steaming vat of dye. She lifted it out a minute or two later. It was…copper green?

“Is that dark enough?,” Yondo asked Pinsky.. (Dark enough? It’s GREEN!)

“Well let’s watch it and see how it goes,” said Pinsky, in a soothing tone that suggested there was nothing to fear about that green color. “So this is the oxygenation process,” she continued.

Theresa Yondo, left, and a friend listen to instructions on how to remove their fabric from the vat of indigo dye. There’s a science to it; holding the dye-soaked fabric over the pot to drip adds oxygen to the dye vat, a no-no. It weakens the strength of the dye. [Amy Eddings / ideastream]

“Oh, right, okay, I see, we have to watch,” said Yondo.

“You’ll see, over time — it should just be a minute or so — the green areas will start getting bluer and bluer and bluer…”

Sure enough, they were shading from green to blue, right before our eyes.

“Oh, I see it happening now,” said Yondo. “It’s very deceiving at first.” “And that’s the magic of the indigo dye,” said Pinsky.

Cotton muslin, folded and bound with rubber band in a Japanese tie-dye method called shibori, slowly turn from green to blue in a plastic bin at the Praxis Fiber Workshop. [Amy Eddings / ideastream]

One of the banners is designed by Indiana artist Rowland Ricketts. His design consists of different shades of blue that Pinsky’s workshop attendees will achieve by dipping their cotton squares into the dye vat one to four times, depending on how far they live from the Cuyahoga River.

“With this banner I wanted people just starting to think about the distance between themselves and one really key element of the reason that Cleveland exists as a city in the first place, is its geographical location and the river that’s there,” he said told ideastream, from his studio in Bloomington.

Ricketts sees physical distance as a metaphor for the psychological distance we’ve created between ourselves and the environment, especially the rivers halfway around the globe that we don’t see, smell or drink.

“If we had to make 400 million, 500 million pairs of jeans a year in our own town and deal with all that waste, we wouldn’t be doing it,” Ricketts said. Or we’d be doing it in a very different way and they’d be a lot more expensive.”

We used to think that toxic compounds were diluted and rendered harmless when we flushed them into our waterways. It took the stupefying image of a river catching fire in Cleveland to change that mindset. Could something as commonplace as our blue jeans be the force for change today? Jessica Pinsky said the movement starts with natural indigo.

“The end goal is let’s make natural fabric here in Cleveland that is 100 percent natural, the fibers are grown here, the dye is made here, it’s dyed here, it’s woven here, it’s constructed here, and it is, somehow, affordable, right? That is absolutely the long term goal,” she said.

Volunteers stitch together hundreds of indigo-dyed cotton squares into banners at Praxis Fiber Workshop in North Collinwood, June 6, 2019. The three banners will be installed at the Detroit Superior Bridge. [Courtesy of Jessica Pinsky]

Pinsky and her helpers begin installing the indigo banners on the Detroit Superior Bridge Monday. The best place to see them is from Settlers Landing Park on the east bank of the Flats. They’ll hang there until June 24. And for those who want get their hands blue, Praxis has an indigo dyeing class in July.

An example of shibori, a Japanese tie-dyeing technique, lies beneath a pleated and folded bundle of plain cotton muslin. The folding method produces the geometric patterns seen in the finished sample. [Amy Eddings / ideastream]

To read the full article and listen to the audio please visit ideastream.org

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2021

Categories |

© PraxisFiberWorkshop. All rights reserved.

Praxis Fiber Workshop is a 501C3 non-profit and all contributions are tax-deductible within the provisions of the law

RSS Feed

RSS Feed